What Are We Doing with All These Tests? (And, Refactoring)

Now that we’ve seen the basics of TDD in action, it’s time to pause and talk about why we’re doing it.

I’m imagining several of you, dear readers, have been holding back some seething frustration—perhaps some of you have done a bit of unit testing before, and perhaps some of you are just in a hurry. You’ve been biting back questions like:

-

Aren’t all these tests a bit excessive?

-

Surely some of them are redundant? There’s duplication between the functional tests and the unit tests.

-

Those unit tests seemed way too trivial—testing a one-line function that returns a constant! Isn’t that just a waste of time? Shouldn’t we save our tests for more complex things?

-

What about all those tiny changes during the unit-test/code cycle? Couldn’t we just skip to the end? I mean,

home_page = None!? Really? -

You’re not telling me you actually code like this in real life?

Ah, young grasshopper. I too was once full of questions like these. But only because they’re perfectly good questions. In fact, I still ask myself questions like these, all the time. Does all this stuff really have value? Is this a bit of a cargo cult?

Programming Is Like Pulling a Bucket of Water Up from a Well

Ultimately, programming is hard. Often, we are smart, so we succeed. TDD is there to help us out when we’re not so smart. Kent Beck (who basically invented TDD) uses the metaphor of lifting a bucket of water out of a well with a rope: when the well isn’t too deep, and the bucket isn’t very full, it’s easy. And even lifting a full bucket is pretty easy at first. But after a while, you’re going to get tired. TDD is like having a ratchet that lets you save your progress, so you can take a break, and make sure you never slip backwards.

That way you don’t have to be smart all the time.

OK, perhaps in general, you’re prepared to concede that TDD is a good idea, but maybe you still think I’m overdoing it? Testing the tiniest thing, and taking ridiculously many small steps?

TDD is a discipline, and that means it’s not something that comes naturally; because many of the payoffs aren’t immediate but only come in the longer term, you have to force yourself to do it in the moment. That’s what the image of the Testing Goat is supposed to represent—you need to be a bit bloody-minded about it.

Now, let us return to our muttons.

Using Selenium to Test User Interactions

Where were we at the end of the last chapter? Let’s rerun the test and find out:

$ python functional_tests.py

F

======================================================================

FAIL: test_can_start_a_todo_list

(__main__.NewVisitorTest.test_can_start_a_todo_list)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "...goat-book/functional_tests.py", line 21, in

test_can_start_a_todo_list

self.fail("Finish the test!")

AssertionError: Finish the test!

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 1.609s

FAILED (failures=1)

Did you try it, and get an error saying Problem loading page or

Unable to connect? So did I. It’s because we forgot to spin up the dev

server first using manage.py runserver. Do that, and you’ll get the failure

message we’re after.

| One of the great things about TDD is that you never have to worry about forgetting what to do next—just rerun your tests and they will tell you what you need to work on. |

“Finish the test”, it says, so let’s do just that! Open up functional_tests.py and we’ll extend our FT:

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

from selenium.webdriver.common.keys import Keys

import time

import unittest

class NewVisitorTest(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

self.browser = webdriver.Firefox()

def tearDown(self):

self.browser.quit()

def test_can_start_a_todo_list(self):

# Edith has heard about a cool new online to-do app.

# She goes to check out its homepage

self.browser.get("http://localhost:8000")

# She notices the page title and header mention to-do lists

self.assertIn("To-Do", self.browser.title)

header_text = self.browser.find_element(By.TAG_NAME, "h1").text (1)

self.assertIn("To-Do", header_text)

# She is invited to enter a to-do item straight away

inputbox = self.browser.find_element(By.ID, "id_new_item") (1)

self.assertEqual(inputbox.get_attribute("placeholder"), "Enter a to-do item")

# She types "Buy peacock feathers" into a text box

# (Edith's hobby is tying fly-fishing lures)

inputbox.send_keys("Buy peacock feathers") (2)

# When she hits enter, the page updates, and now the page lists

# "1: Buy peacock feathers" as an item in a to-do list table

inputbox.send_keys(Keys.ENTER) (3)

time.sleep(1) (4)

table = self.browser.find_element(By.ID, "id_list_table")

rows = table.find_elements(By.TAG_NAME, "tr") (1)

self.assertTrue(any(row.text == "1: Buy peacock feathers" for row in rows))

# There is still a text box inviting her to add another item.

# She enters "Use peacock feathers to make a fly"

# (Edith is very methodical)

self.fail("Finish the test!")

# The page updates again, and now shows both items on her list

[...]| 1 | We’re using the two methods that Selenium provides to examine web pages:

find_element and find_elements

(notice the extra s,

which means it will return several elements rather than just one).

Each one is parameterized with a By.SOMETHING

which lets us search using different HTML properties and attributes. |

| 2 | We also use send_keys,

which is Selenium’s way of typing into input elements. |

| 3 | The Keys class (don’t forget to import it)

lets us send special keys like Enter.[1] |

| 4 | When we hit Enter, the page will refresh.

The time.sleep is there to make sure the browser has finished loading

before we make any assertions about the new page.

This is called an "explicit wait"

(a very simple one; we’ll improve it in [chapter_06_explicit_waits_1]). |

Watch out for the difference between the Selenium find_element()

and find_elements() functions.

One returns an element and raises an exception if it can’t find it,

whereas the other returns a list, which may be empty.

|

Also, just look at that any() function.

It’s a little-known Python built-in.

I don’t even need to explain it, do I?

Python is such a joy.[2]

If you’re one of my readers who doesn’t know Python,

what’s happening inside the any() may need some explaining.

The basic syntax is that of a list comprehension,

and if you haven’t learned about them, you should do so immediately!

Trey Hunner’s explanation is excellent.

In point of fact, because we’re omitting the square brackets,

we’re actually using a generator expression rather than a list comprehension.

It’s probably less important to understand the difference between those two,

but if you’re curious, check out this

blog post by Guido himself

explaining the difference.

|

Let’s see how it gets on:

$ python functional_tests.py [...] selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate element: h1; For documentation on this error, please visit: [...]

Decoding that,

the test is saying it can’t find an <h1> element on the page.

Let’s see what we can do to add that to the HTML of our home page.

Big changes to a functional test are usually a good thing to commit on their own. I failed to do so when I was first working out the code for this chapter, and I regretted it later when I changed my mind and had the change mixed up with a bunch of others. The more atomic your commits, the better:

$ git diff # should show changes to functional_tests.py $ git commit -am "Functional test now checks we can input a to-do item"

The “Don’t Test Constants” Rule, and Templates to the Rescue

Let’s take a look at our unit tests, lists/tests.py. Currently we’re looking for specific HTML strings, but that’s not a particularly efficient way of testing HTML. In general, one of the rules of unit testing is Don’t test constants, and testing HTML as text is a lot like testing a constant.

In other words, if you have some code that says:

wibble = 3There’s not much point in a test that says:

from myprogram import wibble

assert wibble == 3Unit tests are really about testing logic, flow control, and configuration. Making assertions about exactly what sequence of characters we have in our HTML strings isn’t doing that.

It’s not quite that simple, since HTML is code after all, and we do want something to check that we’ve written code that works, but that’s our FT’s job, not the unit tests'.

In any case, mangling raw strings in Python really isn’t a great way of dealing with HTML. There’s a much better solution, which is to use templates. Quite apart from anything else, if we can keep HTML to one side in a file whose name ends in .html, we’ll get better syntax highlighting! There are lots of Python templating frameworks out there, and Django has its own which works very well. Let’s use that.

Refactoring to Use a Template

What we want to do now is make our view function return exactly the same HTML, but just using a different process. That’s a refactor—when we try to improve the code without changing its functionality.

That last bit is really important. If you try to add new functionality at the same time as refactoring, you’re much more likely to run into trouble. Refactoring is actually a whole discipline in itself, and it even has a reference book: Martin Fowler’s Refactoring.

The first rule is that you can’t refactor without tests. Thankfully, we’re doing TDD, so we’re way ahead of the game. Let’s check that our tests pass; they will be what makes sure that our refactoring is behaviour-preserving:

$ python manage.py test [...] OK

Great! We’ll start by taking our HTML string and putting it into its own file. Create a directory called lists/templates to keep templates in, and then open a file at lists/templates/home.html, to which we’ll transfer our HTML:[3]

<html>

<title>To-Do lists</title>

</html>Mmmh, syntax-highlighted…much nicer! Now to change our view function:

from django.shortcuts import render

def home_page(request):

return render(request, "home.html")Instead of building our own HttpResponse, we now use the Django render()

function. It takes the request as its first parameter (for reasons we’ll go

into later) and the name of the template to render. Django will automatically

search folders called templates inside any of your apps' directories. Then

it builds an HttpResponse for you, based on the content of the template.

Templates are a very powerful feature of Django’s,

and their main strength consists of substituting Python variables into HTML text.

We’re not using this feature yet, but we will in future chapters.

That’s why we use render() rather than, say,

manually reading the file from disk with the built-in open().

|

Let’s see if it works:

$ python manage.py test

[...]

======================================================================

ERROR: test_home_page_returns_correct_html

(lists.tests.HomePageTest.test_home_page_returns_correct_html) (2)

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "...goat-book/lists/tests.py", line 7, in test_home_page_returns_correct_html

response = self.client.get("/") (3)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

[...]

File "...goat-book/lists/views.py", line 4, in home_page

return render(request, "home.html") (4)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

File ".../django/shortcuts.py", line 24, in render

content = loader.render_to_string(template_name, context, request, using=using)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

File ".../django/template/loader.py", line 61, in render_to_string

template = get_template(template_name, using=using)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

File ".../django/template/loader.py", line 19, in get_template

raise TemplateDoesNotExist(template_name, chain=chain)

django.template.exceptions.TemplateDoesNotExist: home.html (1)

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.074s

Another chance to analyse a traceback:

| 1 | We start with the error: it can’t find the template. |

| 2 | Then we double-check what test is failing: sure enough, it’s our test of the view HTML. |

| 3 | Then we find the line in our tests that caused the failure: it’s when we request the root URL ("/"). |

| 4 | Finally, we look for the part of our own application code that caused the

failure: it’s when we try to call render. |

So why can’t Django find the template? It’s right where it’s supposed to be, in the lists/templates folder.

The thing is that we haven’t yet officially registered our lists app with Django.

Unfortunately, just running the startapp command

and having what is obviously an app in your project folder

isn’t quite enough.

You have to tell Django that you really mean it,

and add it to settings.py as well. Belt and braces.

Open it up and look for a variable called INSTALLED_APPS,

to which we’ll add lists:

# Application definition

INSTALLED_APPS = [

"django.contrib.admin",

"django.contrib.auth",

"django.contrib.contenttypes",

"django.contrib.sessions",

"django.contrib.messages",

"django.contrib.staticfiles",

"lists",

]You can see there’s lots of apps already in there by default. We just need to add ours to the bottom of the list. Don’t forget the trailing comma—it may not be required, but one day you’ll be really annoyed when you forget it and Python concatenates two strings on different lines…

Now we can try running the tests again:

$ python manage.py test [...] OK

Our refactor of the code is now complete, and the tests mean we’re happy that behaviour is preserved. Now we can change the tests so that they’re no longer testing constants; instead, they should just check that we’re rendering the right template.

Checking template rendering

The Django test client has a method, assertTemplateUsed, which can do just what we want:

def test_home_page_returns_correct_html(self):

response = self.client.get("/")

self.assertContains(response, "<title>To-Do lists</title>") (1)

self.assertContains(response, "<html>")

self.assertContains(response, "</html>")

self.assertTemplateUsed(response, "home.html") (2)| 1 | We’ll leave the old tests there for now, just to make sure everything is working the way we think it is. |

| 2 | .assertTemplateUsed lets us check what template was used to render a response

(NB: it will only work for responses that were retrieved by the test client). |

And that test will still pass:

Ran 1 tests in 0.016s OK

Just because I’m always suspicious of a test I haven’t seen fail, let’s deliberately break it:

self.assertTemplateUsed(response, "wrong.html")That way we’ll also learn what its error messages look like:

AssertionError: False is not true : Template 'wrong.html' was not a template used to render the response. Actual template(s) used: home.html

That’s very helpful! Let’s change the assert back to the right thing. While we’re at it, we can delete our old assertions, and give the test method a more specific name:

from django.test import TestCase

class HomePageTest(TestCase):

def test_uses_home_template(self):

response = self.client.get("/")

self.assertTemplateUsed(response, "home.html")The main point, though, is that instead of testing constants we’re testing our implementation. Great!

On Refactoring

That was an absolutely trivial example of refactoring. But, as Kent Beck puts it in Test-Driven Development: By Example, "Am I recommending that you actually work this way? No. I’m recommending that you be able to work this way".

In fact, as I was writing this my first instinct was to dive in

and change the test first—make it

use the assertTemplateUsed function straight away;

delete the three superfluous assertions,

leaving just a check of the contents

against the expected render;

and then go ahead and make the code change.

But notice how that actually would have left space

for me to break things:

I could have defined the template as containing any arbitrary string,

instead of the string with the right <html> and <title> tags.

| When refactoring, work on either the code or the tests, but not both at once. |

There’s always a tendency to skip ahead a couple of steps, to make a couple of tweaks to the behaviour while you’re refactoring, but pretty soon you’ve got changes to half a dozen different files, you’ve totally lost track of where you are, and nothing works any more. If you don’t want to end up like Refactoring Cat (Refactoring Cat—be sure to look up the full animated GIF (source: 4GIFs.com)), stick to small steps; keep refactoring and functionality changes entirely separate.

| We’ll come across “Refactoring Cat” again during this book, as an example of what happens when we get carried away and want to change too many things at once. Think of it as the little cartoon demon counterpart to the Testing Goat, popping up over your other shoulder and giving you bad advice. |

It’s a good idea to do a commit after any refactoring:

$ git status # see tests.py, views.py, settings.py, + new templates folder $ git add . # will also add the untracked templates folder $ git diff --staged # review the changes we're about to commit $ git commit -m "Refactor home page view to use a template"

A Little More of Our Front Page

In the meantime, our functional test is still failing. Let’s now make an actual code change to get it passing. Because our HTML is now in a template, we can feel free to make changes to it, without needing to write any extra unit tests.

| This is another distinction between FTs and unit tests; Because the FTs use a real web browser, we use them as the primary tool for testing our UI, and the HTML that implements it. |

So, wanted an <h1>:

<html>

<head>

<title>To-Do lists</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Your To-Do list</h1>

</body>

</html>Let’s see if our functional test likes it a little better:

selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate element: [id="id_new_item"]; For documentation on this error, [...]

OK, let’s add an input with that ID:

[...]

<body>

<h1>Your To-Do list</h1>

<input id="id_new_item" />

</body>

</html>And now what does the FT say?

AssertionError: '' != 'Enter a to-do item'

We add our placeholder text…

<input id="id_new_item" placeholder="Enter a to-do item" />Which gives:

selenium.common.exceptions.NoSuchElementException: Message: Unable to locate element: [id="id_list_table"]; [...]

So we can go ahead and put the table onto the page. At this stage it’ll just be empty:

<input id="id_new_item" placeholder="Enter a to-do item" />

<table id="id_list_table">

</table>

</body>What does the FT think?

File "...goat-book/functional_tests.py", line 40, in

test_can_start_a_todo_list

self.assertTrue(any(row.text == "1: Buy peacock feathers" for row in rows))

AssertionError: False is not true

Slightly cryptic!

We can use the line number to track it down,

and it turns out it’s that any() function I was so smug about earlier—or,

more precisely, the assertTrue, which doesn’t have a very explicit failure message.

We can pass a custom error message as an argument to most assertX methods in unittest:

self.assertTrue(

any(row.text == "1: Buy peacock feathers" for row in rows),

"New to-do item did not appear in table",

)If you run the FT again, you should see our helpful message:

AssertionError: False is not true : New to-do item did not appear in table

But now, to get this to pass, we will need to actually process the user’s form submission. And that’s a topic for the next chapter.

For now let’s do a commit:

$ git diff $ git commit -am "Front page HTML now generated from a template"

Thanks to a bit of refactoring, we’ve got our view set up to render a template, we’ve stopped testing constants, and we’re now well placed to start processing user input.

Recap: The TDD Process

We’ve now seen all the main aspects of the TDD process, in practice:

-

Functional tests

-

Unit tests

-

The unit-test/code cycle

-

Refactoring

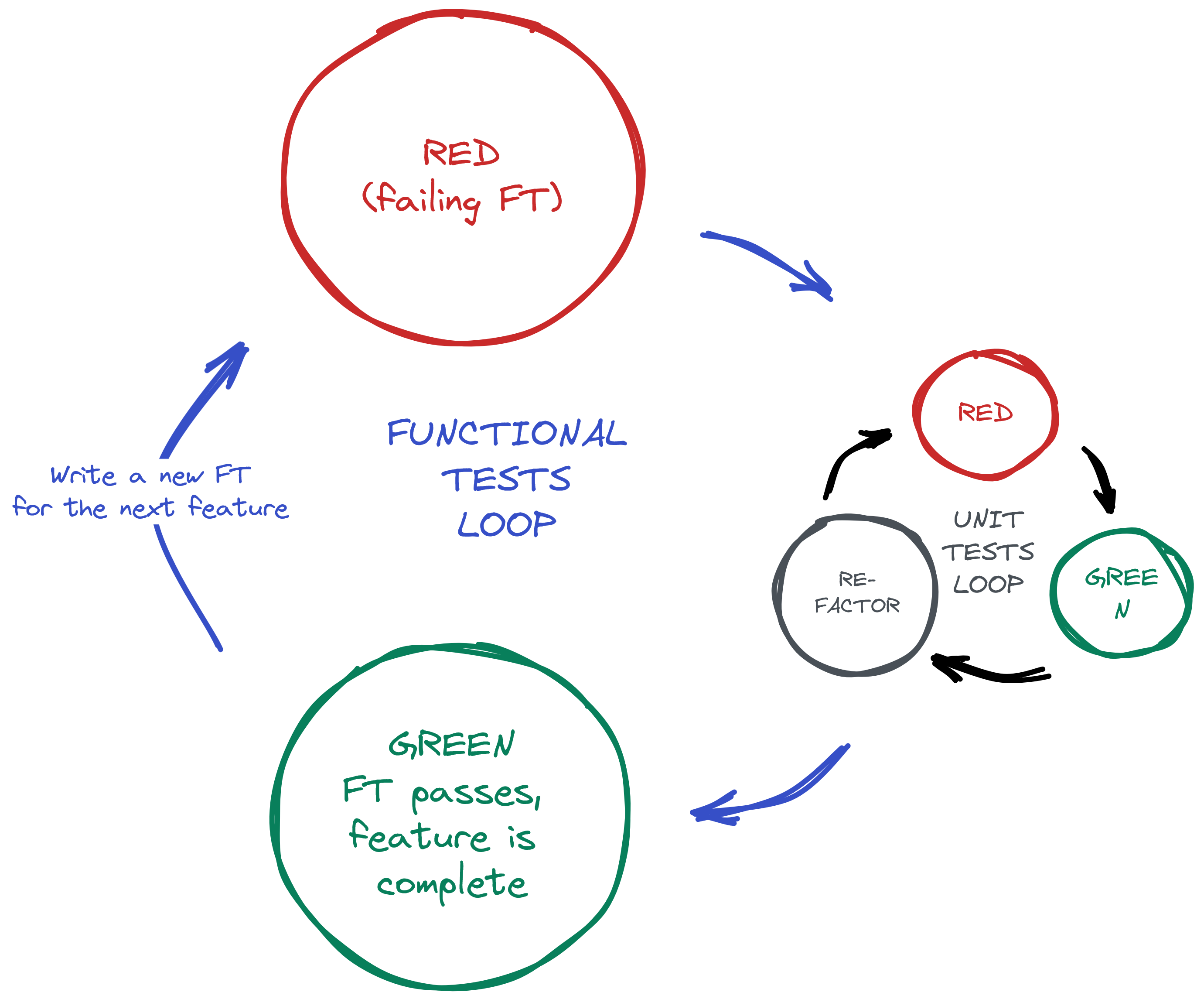

It’s time for a little recap, and perhaps even some flowcharts (forgive me, my years misspent as a management consultant have ruined me. On the plus side, said flowcharts will feature recursion!)

What does the overall TDD process look like?

-

We write a test.

-

We run the test and see it fail.

-

We write some minimal code to get it a little further.

-

We rerun the test and repeat until it passes (the unit test / code cycle)

-

Then, we look for opportunities to refactor our code, using our tests to make sure we don’t break anything.

-

And start again from the top!

It’s very common to talk about this process using the three words Red, Green, Refactor. See Red, Green, Refactor.

-

We write a test, and see it fail ("Red").

-

We cycle between code and tests until the test passes: "Green".

-

Then, we look for opportunities to refactor.

-

Repeat as required!

Double-loop TDD

But how does this apply when we have functional tests and unit tests? Well, you can think of the functional test as driving a higher-level version of the same cycle, with an inner red/green/refactor loop being required to get an FT from Red to Green; see ee Double-Loop TDD: Inner and Outer Loops.

When a new feature or business requirement comes along, we write a new (failing) FT to capture a high level view of the requirement. It may not cover every last edge case, but it should be enough to reassure ourselves that things are working.

To get that functional test to green, we then enter into the lower-level unit tests cycle, where we put together all the moving parts required, add tests for all the edge cases. Any time we get to green & refactored at the unit tests level, we can pop back up to the FT level to guide us towards the next thing we need to work. Once both levels are green, we can do any extra refactoring or work on edge cases.

We’ll explore all of the different parts of this workflow in more detail over the coming chapters.

Comments